How Our Brain Recognizes Faces: Rethinking Spatial Frequency Processing

When we see an object, our brain doesn’t process all the details at once but instead builds a representation step by step. Traditional models suggest that recognition starts with broad, low-detail information (low spatial frequency, LSF) before integrating finer details (high spatial frequency, HSF). But is this true also for face perception? In the case of faces, our research suggests that this process is more flexible than previously thought.

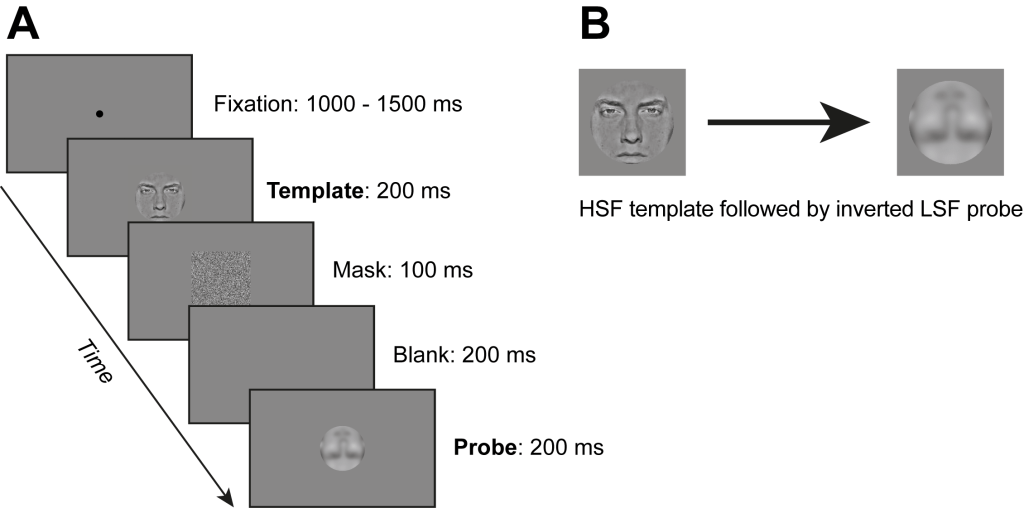

In two experiments, we tested how spatial frequency contributes to face recognition by leveraging the face inversion effect, where recognizing upside-down faces is much harder. Participants matched faces that were either familiar or unfamiliar, with images containing either the same SF information (congruent) or complementary SF (incongruent). While high-frequency details generally improved accuracy, LSF helped only when paired with HSF templates (the first stimulus presented) and in certain conditions —only for upright, familiar faces. Unfamiliar faces, on the other hand, were simply easier to recognize when both images contained the same spatial frequency, regardless of whether they emphasized fine details or coarse structure.

In the figure above, a brief depiction of the paradigm used in Experiment 1 (familiar faces) and Experiment 2 (familiar vs. unfamiliar faces).

These findings challenge the idea that LSF always provides a foundational template for face recognition. Instead, spatial frequency processing appears to be experience-dependent and task-specific, with the brain adapting its strategy based on familiarity. This insight reshapes how we understand face perception, with implications for vision science and artificial recognition systems alike.

You can read the whole article here or listen to a podcast here.

Dr Antimo Buonocore

Dr Antimo Buonocore